A bipv system (Building-Integrated Photovoltaics) is a sophisticated engineering solution where photovoltaic modules function as both the building’s outer skin and its primary energy generator. Unlike traditional solar setups, a complete bipv system integrates solar cells into structural elements like facades, curtain walls, and roof tiles, working in tandem with inverters, energy management software, and specialized mounting hardware to create a seamless energy-producing envelope. By replacing conventional materials with active solar glass or membranes, these systems provide vital functions—thermal insulation, weatherproofing, and noise reduction—while generating clean electricity directly at the point of consumption, effectively turning the building into a self-sustaining power plant.

I still remember the first time I stood behind a massive BIPV curtain wall during installation. From the outside, it looked like a sleek, dark glass monolith. But from the inside? It was a maze of cables and micro-inverters tucked neatly into the aluminum mullions. It’s a bit like looking under the hood of a luxury electric car; it looks simple on the surface, but the engineering underneath is what makes the magic happen.

If you searched “bipv system”, you probably want the real breakdown: what parts exist, how they connect, and how integration differs by façade/roof/skylight/shading—without marketing fog. That’s what we’ll do here.

Table of Contents

Featured-snippet

A BIPV system includes

- BIPV building products (PV modules/tiles/glazing used as envelope elements)

- mounting + weatherproofing interfaces (facade/roof details)

- DC electrical BOS (strings, protection, cabling)

- inverters + AC integration (switchgear, metering)

- monitoring + safety measures—designed to satisfy both electrical requirements and building-performance requirements. Standards like IEC 63092 specifically address PV modules used as building products.

The "Guts" of the BIPV System: Core Components

When we talk about a bipv system, we aren’t just talking about a panel. We are talking about a coordinated ecosystem.

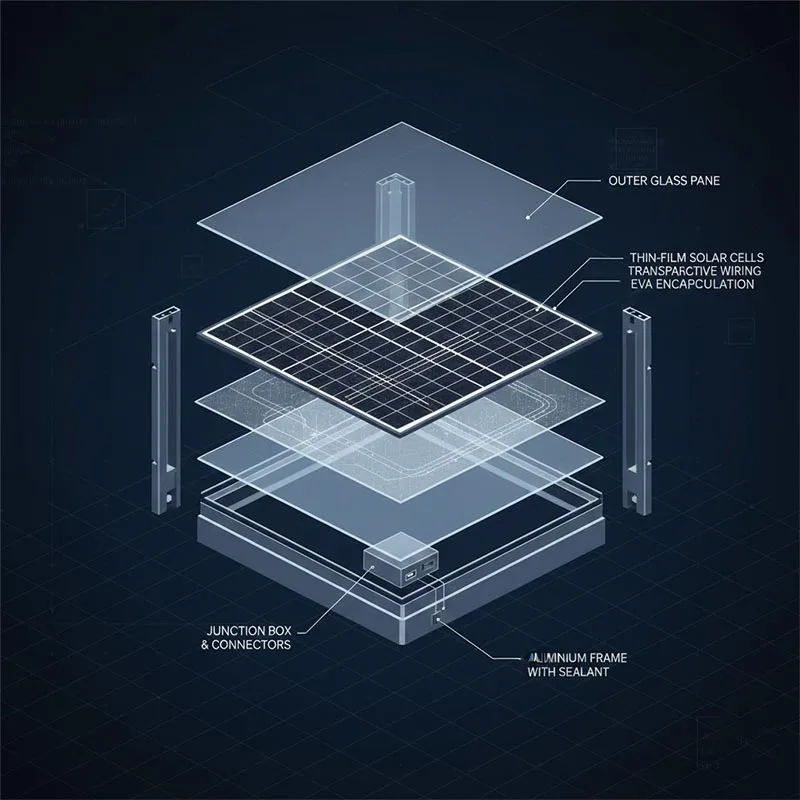

The PV Module (The “Skin”): Whether it’s crystalline silicon or thin-film, this is the part that catches the photons. In BIPV, this glass must meet architectural safety standards (tempered or laminated) just like any other window.

The Inverter (The “Brain”): This turns the DC power from the sun into the AC power your laptop uses. In many BIPV projects, I prefer using micro-inverters or power optimizers. Why? Because if one part of a tall building is shaded by a neighboring tower, a micro-inverter ensures the rest of the wall keeps pumping out power. It’s like having a team where one person’s bad day doesn’t ruin the whole department’s output.

BOS (Balance of System): This includes the cables, connectors (usually MC4), and combiners. In BIPV, these are “hidden” within the building’s frame.

Expert Tip: Never overlook the “junction box.” In standard solar, it’s on the back. In BIPV, we often use “edge-positioned” junction boxes so they disappear into the window frame. If you can see the wires, the architect isn’t going to be happy!

BIPV vs BAPV

Here’s a line I use when a project team is confused:

BAPV (building-applied PV): PV is added on top of the building (typical rooftop racks).

BIPV: PV is part of the building—remove it and you must replace it with another building product.

IEA PVPS Task 15’s definition is very direct: a BIPV module is both a PV module and a construction product, designed as a building component.

That one definition is the reason BIPV projects live or die based on façade detailing, not just electrical design.

What a BIPV system is made of

I’ll give you the “engineer’s view” first, then we’ll translate it into integration methods.

Core bill-of-systems (BoS) in a typical grid-connected BIPV system

| Subsystem | What it includes | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| BIPV building products | BIPV modules (opaque, semi-transparent), PV tiles/shingles, PV glazing units | Must meet both PV output and building performance |

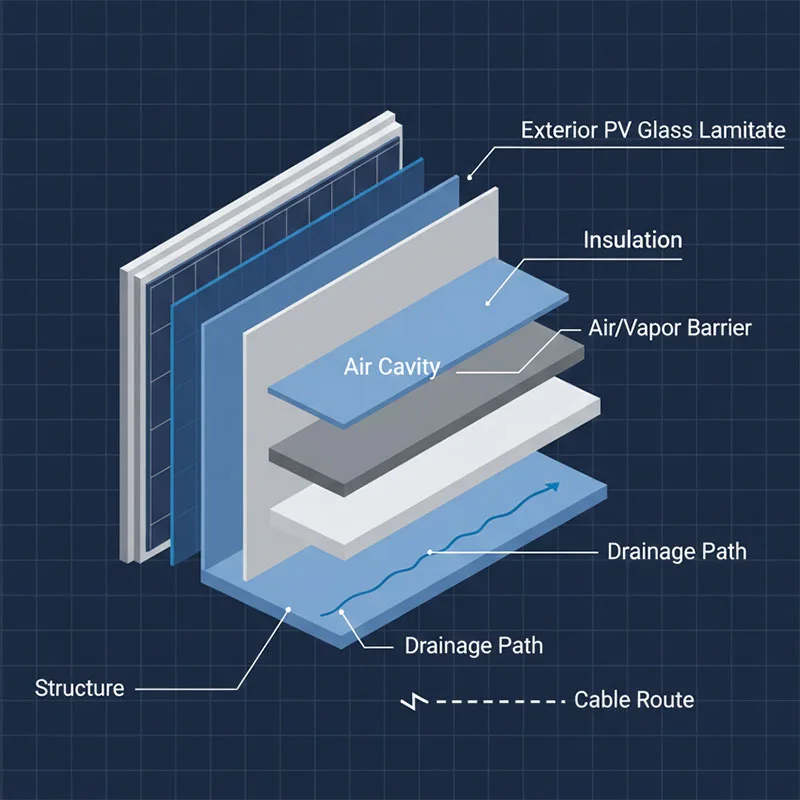

| Envelope interfaces | Substructure, brackets/rails, gaskets, sealants, drainage paths, vapour/air barriers | Most failures are here (leaks, thermal bridges, tolerances) |

| DC side | String wiring, combiner boxes (if used), DC isolators, fuses, SPD, conduits, cable trays | Safety + maintainability; fire risk control |

| Inverters + AC integration | Inverters (string/micro/central), AC isolators, switchgear, metering, grid connection | Where PV becomes usable building power |

| Monitoring & controls | Data loggers, irradiance/temp sensors (optional), alarms, dashboards | Keeps “green claims” measurable (EEAT-friendly) |

A small personal note: I’ve seen BIPV projects where everything looked perfect on renderings—then six months after handover, nobody knew which facade zone was underperforming because monitoring was treated as “nice to have.” That moment is… awkward. And expensive. Monitoring is not decoration.

System architecture

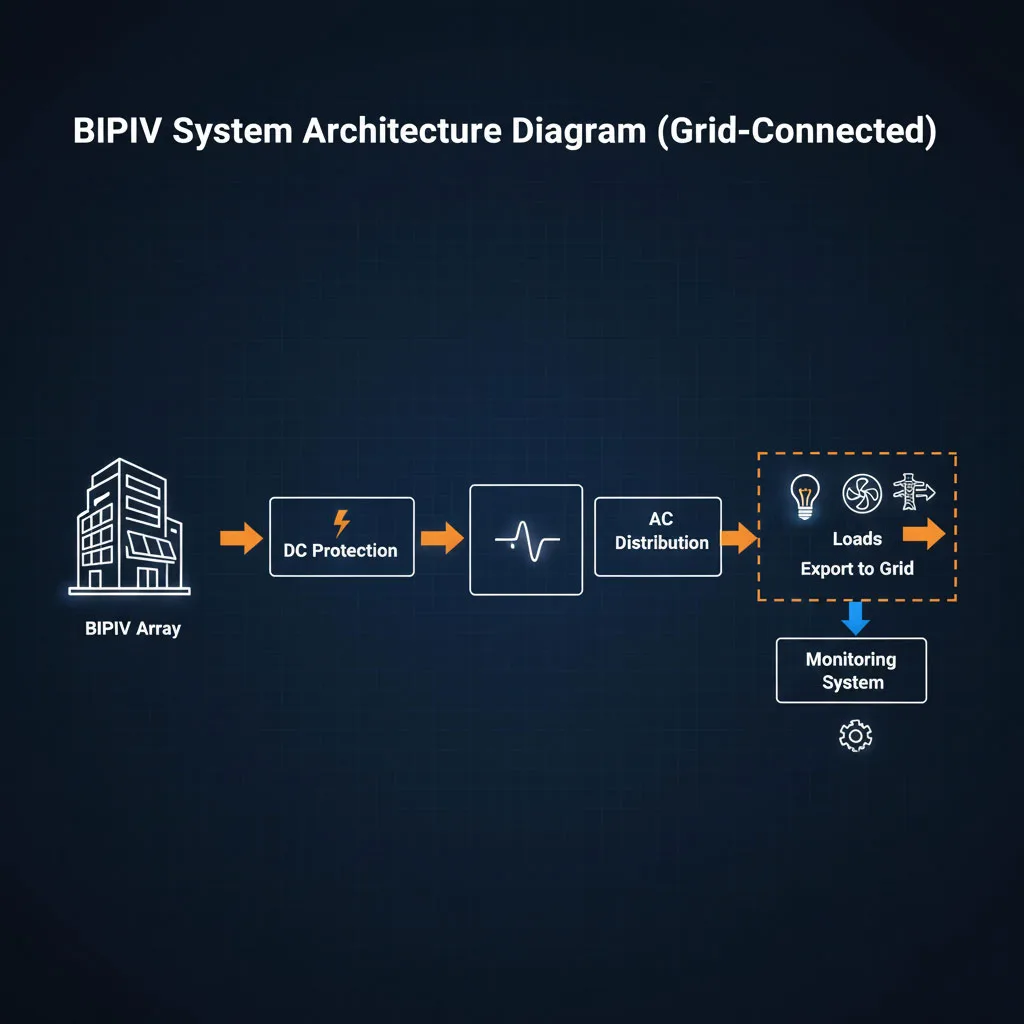

Most commercial BIPV systems are grid-connected (simpler, less space, fewer batteries). Typical architecture:

BIPV array (façade/roof) → DC protection → inverter(s) → AC distribution → building loads / export → monitoring

This is consistent with classic PV integration guidance in NREL’s BIPV references and sourcebooks.

Inverter choices

String inverters: common baseline; good for grouped facade zones.

Module-level power electronics (MLPE): useful when façade has complex shading patterns (balconies, fins, neighboring towers).

Central inverters: typically for very large uniform arrays (less common for facade-heavy BIPV).

The “right answer” depends on shading, access, replacement strategy, and electrical zoning—not just efficiency.

Integration methods

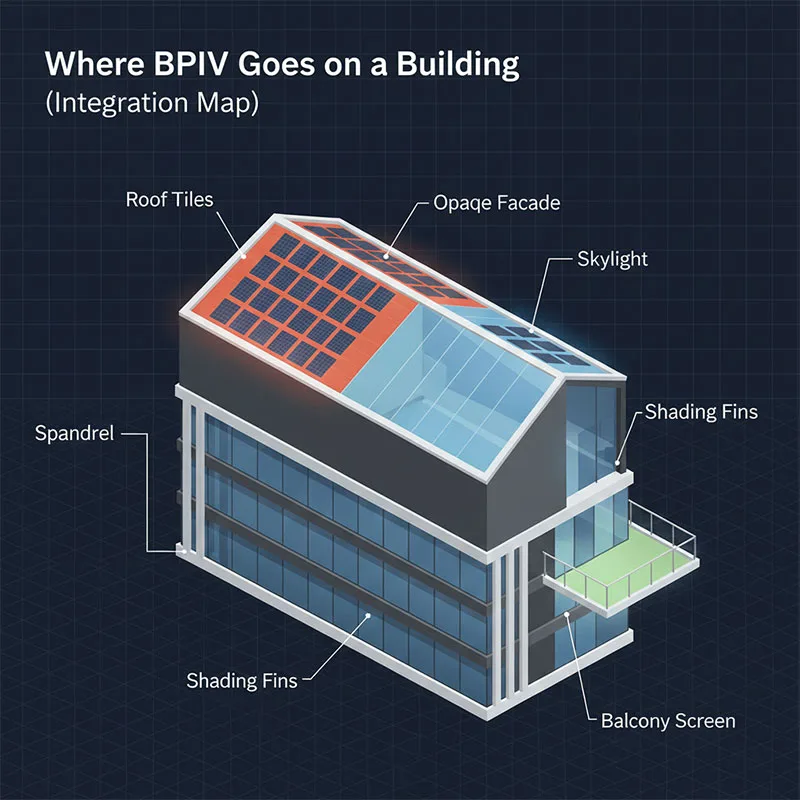

NREL’s early BIPV guidance groups systems broadly into façade systems and roofing systems, with façade including curtain wall products, spandrels, and glazings; roofing including tiles/shingles/standing seam/skylights.

I’ll expand that into four practical buckets:

A. Roof-integrated BIPV (tiles, shingles, standing seam, roof membranes)

Best when: low-rise / roof has good solar access.(BIPV Roof System)

Key engineering focus: waterproofing layers, wind uplift, maintainability.

Even here, BIPV is not “rack PV but prettier”—it’s roof construction.

B. BIPV Facade System (curtain wall, spandrel panels, rainscreen cladding)

Best when: high-rise, dense city, limited roof.

Key engineering focus:

Unitized curtain wall tolerances (module dimensions must match facade grids)

Drainage / pressure-equalization strategies

Thermal + condensation management behind modules

The technology landscape and design options for roof/facade BIPV are widely reviewed in peer-reviewed literature (helpful if you want citations for internal design reviews).

C. BIPV glazing & skylights (semi-transparent PV glass)

Best when: atriums, canopies, daylight-driven spaces.

Key engineering focus: daylight vs power trade-off, glare control, SHGC/U-value targets.

Standards work is active here—ISO/IEC drafts even address evaluation methods for solar heat gain behavior in BIPV modules.

D. Shading-integrated BIPV (louvers, fins, brise-soleil, balcony screens)

Best when: you already need shading for comfort and cooling loads.

Key engineering focus: wind loads, access, wiring routes, and maintenance.

This is one of the most “BIPV-native” applications: the PV isn’t fighting the architecture—it is the architecture.

The standards and compliance layer (EEAT lives here)

IEC 63092: “PV modules used as building products”

IEC 63092-1 specifies requirements for building-integrated PV modules and focuses on properties relevant to basic building requirements plus applicable electrotechnical requirements; mounting structure details are addressed in the series scope.

Fire and electrical safety

A U.S. DOE PV fire safety guideline notes that for BIPV, electrical arc safety can become even more critical because PV replaces roofing/building elements.

And if you need deeper fire-risk research context, institutes like Fraunhofer ISE publish work and guidance around fire risk evaluation and minimization for PV systems.

Design checklist

When I audit BIPV specs, these are the questions that separate “nice concept” from “buildable system”:

Envelope function first: What is the PV replacing—spandrel glass, cladding, skylight, shading? (BIPV must behave like that product.)

Water management: Where does water go in every failure mode (wind-driven rain, blocked weeps, seal aging)?

Thermal/condensation: How is heat and moisture managed behind the PV skin?

Electrical zoning: How are façade zones grouped into strings so maintenance and fault isolation are practical?

Access strategy: How will someone inspect/clean/replace a module safely five years later?

Monitoring scope: What data will prove performance and reveal failures early?

How BIPVSYSTEM typically supports a “real” BIPV system delivery

In practice, clients don’t fail on “PV knowledge.” They fail on interfaces.

So the most useful support is usually:

Module format aligned to facade grids (so procurement and installation don’t become chaos)

Integration packages by application: spandrel / canopy / skylight / shading / cladding

Documentation that survives value engineering: details, wiring routes, isolation points, commissioning checklist

Honest boundaries: if something depends on climate/structure/aesthetics, we label it typical / common / customizable and state the decision conditions

That’s how you keep BIPV from being a “demo” and turn it into an asset.

FAQ (People Also Ask)

What is a BIPV system?

A BIPV system is a PV power system where PV modules are integrated into the building envelope (façade, roof, skylight, shading) and replace conventional construction materials while generating electricity.

What are the main components of a BIPV system?

Typical components include BIPV building products, mounting/weatherproofing interfaces, DC protection and wiring, inverters and AC integration, and monitoring/safety systems.

How is a BIPV system different from rooftop PV (BAPV)?

BAPV is added onto a building, while BIPV is part of the building construction product—if removed, it must be replaced by another building element.

What are the most common BIPV integration methods?

Common methods include façade systems (curtain wall, spandrel, glazing) and roofing systems (tiles, shingles, standing seam, skylights), plus shading-integrated PV such as fins and screens.

Which standards apply to BIPV modules used as building products?

IEC 63092-1 specifies requirements for building-integrated PV modules used as building products, focusing on building-relevant properties and electrotechnical requirements.

What are the biggest technical risks in BIPV systems?

Key risks include waterproofing/drainage failures at envelope interfaces, thermal/condensation issues behind modules, electrical safety (arcing/DC isolation), fire strategy, and lack of maintenance access and monitoring.

At BIPVSYSTEM, we’ve mastered the “invisible engineering” that makes solar architecture possible. We don’t just sell components; we design the systems that let your building power itself.

Would you like me to provide a CAD detail for a specific BIPV curtain wall joint to show you exactly how we hide the wiring?